Surprising discovery about nature of CASK gene disorders may influence potential treatments

Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC scientists determine CASK gene disorder is defined by damage to neurons, not the developmental course of the disease

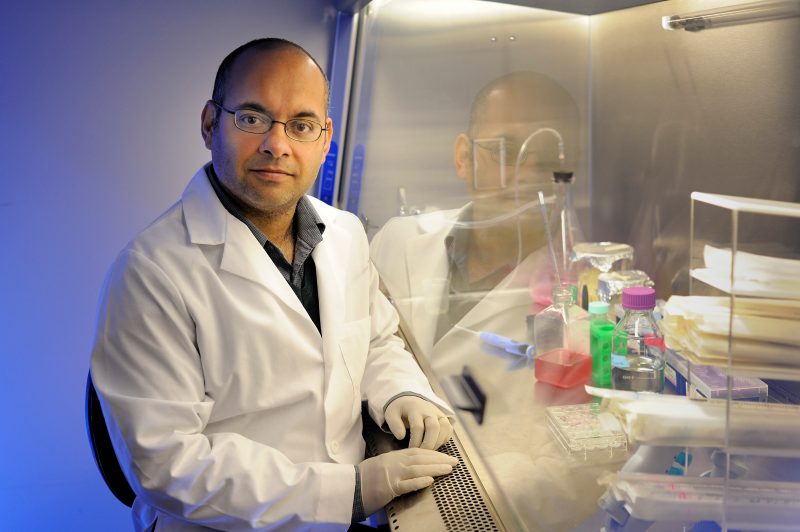

Konark Mukherjee, an assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, led research that challenges traditional understanding of CASK gene disorders.

Virginia Tech researchers publishing in the Journal of Medical Genetics made a discovery about a genetic form of microcephaly - a condition where babies' heads and brains are smaller and grow more slowly than those of unaffected children. The finding has potential to inform treatment strategies.

The researchers, led by Konark Mukherjee, assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, conducted a post-mortem examination of a two-month-old boy with a mutation in the CASK gene. In addition, the scientists designed and executed genetic experiments in mice to provide evidence that loss of CASK function does not affect normal brain development but rather leads to an early loss and degeneration of existing neurons.

“This completely changes the way we think about intervening in CASK disorders. With the understanding that the symptoms result from loss of neurons, it becomes crucial to figure out the toxic biochemical process that is killing the neurons and to stop it,” Mukherjee said. “Such an approach, together with neuro-rehabilitative therapies, may offer real hope in the future. It is extremely likely similar mechanisms also operate in other X-chromosome-linked conditions, like Rett syndrome, which may better explain the regression seen in such cases.”

The post-mortem examination of the 2-month-old boy was done in collaboration with clinical geneticist Ingrid Cristian and autopsy pathologist Julia Hegert of Orlando Health. Surprisingly, the boy’s brain did not exhibit any evidence of disturbed neuronal development but rather characteristics of neurodegeneration.

Using an engineered mouse model, Mukherjee’s research team was able to validate that loss of CASK gene function results in rapid neurodegeneration. Further, they were able to demonstrate that presence of a single intact copy of the gene was sufficient to prevent this degenerative process in females.

Overall, the researchers said deletion of CASK does not appear to affect brain development per se, and the symptoms seem to result from loss of neurons rather than simply loss of the molecule. Future work could begin to consider interventions to help the degenerating cells stay healthy in hopes of preserving some function.

The finding further suggests that the apparent non-degenerative clinical course of this disorder in girls is more likely because of X-linked gene expression. X-linked is a trait involving a gene located on the X chromosome. In an X-linked disease, males are usually affected more profoundly because they only have a single copy of the X chromosome that carries the mutation. In females, the effect of the mutation may be tempered by the second healthy copy on the X chromosome.

The mother of the 2-month-old contacted Mukherjee after the child’s death, saying she wished to donate the body to science to help children and their families who are coping with this rare genetic disease.

Mukherjee leads one of the few research laboratories in the world studying the neuropathology associated with the CASK gene.

“The disorder is so extremely rare, it is very uncommon to have an opportunity to make this kind of discovery,” Mukherjee said. “We all are grateful to the mother of the child and will continue to work hard.”

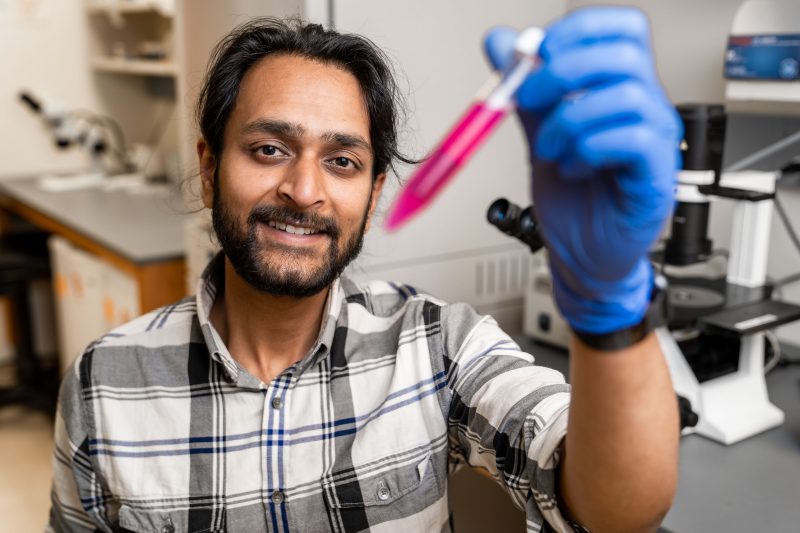

“The field of genetic neurological disorders has been plagued by an incongruence between data from animal models and actual human cases,” said Paras Patel, the study’s first author and a student in Virginia Tech’s Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health Graduate Program. “Our study is unique in that it melds these two avenues of investigation to offer both mechanistic insights and directly applicable findings for humans suffering from the disorder.”

The study also included Virginia Tech researchers Alicia Kerr, a former postdoctoral associate witht the research institute; Leslie LaConte, a research associate professor at the institute and assistant dean for research at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; Michael Fox, a professor at the research institute and director of the School of Neuroscience at the Virginia Tech College of Science; and Sarika Srivastava, a research assistant professor at the institute. The work was supported with funding from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health, the Angelina CASK Neurological Research Foundation, and the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute.

Paras Patel, a student in Virginia Tech's Translational Biology, Medicine and Health Graduate Program and researcher at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, was the first author of a study that offers new insights into CASK gene disorders.