Global Change Center undergraduate researchers investigate questions related to environmental change

In a year complicated by the global pandemic, three recipients of Global Change Center Undergraduate Research Grants succeeded in conducting impactful research and presented their work at a campus conference attended by hundreds of Virginia Tech students and faculty.

The Global Change Center at Virginia Tech (GCC), with support from the Fralin Life Sciences Institute, is proud to sponsor undergraduate students and their research projects that align with their mission for advancing collaborative, interdisciplinary approaches to address critical global changes impacting the environment and society.

Omar West, Tess Alexander, and Ash VanWinkle displayed their ability to communicate complex research by presenting at the Dennis Dean Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship Conference, which is held each year in the spring. Each student, under the mentorship of a Global Change Center-affiliated faculty member, showcased their creative and scholarly accomplishments on three diverse research projects.

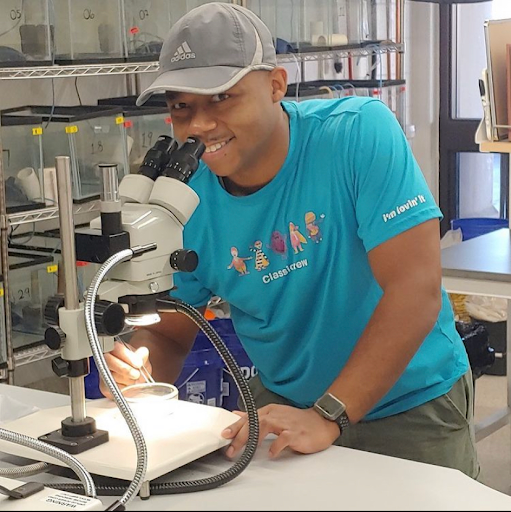

Omar West, who is double majoring in biological sciences and nanomedicine studied the effect of pH and symbiont density on a cleaning symbiosis.

“Omar is the glue that holds everyone in the lab together,” commented GCC affiliate Bryan Brown, an associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science. “As a freshman he worked at McDonald’s to support himself, but the funding from the GCC allowed him to instead focus on his research.”

As a Roanoke native and an accomplished Eagle Scout, Omar West first became fascinated by science at a young age. “Watching science fiction shows and movies opened my eyes to all of the possible technologies that could be created from science,” he said, noting that the importance of research is that it can ultimately benefit humanity.

This fall, West will enter his senior year at Virginia Tech. West first joined the Brown lab as a freshman in 2018 as a biological sciences and nanomedicine double major. Research conducted in the Brown lab broadly focuses on community ecology in aquatic systems by conducting experimental tests of ecological theory, most notably through field experimentation. Initially contributing to many of the lab’s ongoing projects, West developed his independent research project almost two years ago.

The research focused on the cleaning symbiosis between crayfish and worms known as ecosymbiotic annelids. Knowing that worms inhabiting the crayfish play a hygienic role for the crayfish that is mutualistic at low and intermediary levels, Omar wanted to investigate whether changes in water quality, specifically in pH, affect the overall health of a crayfish by shifting the worms to high, or parasitic, levels. The results of the study revealed that relatively basic pH of 8 in combination with an intermediary worm count of 6 led to the greatest survivability of the crayfish and the overall fitness.

Omar is currently participating in a summer REU program with the University of Florida’s Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience in the lab of Sandra Loesgen, an associate professor of chemistry. There, he will conduct assays on microorganisms from jellyfish and bacterial strains from Antarctica.

As for West’s long-term goals, he plans to enter a graduate program upon completion of his degree next year. “Better keep a close eye on me. Because I’m going to change the world someday.”

Does big data bring opportunity, bias, or both for conservation? Tess Alexander explored open access species occurrence data.

The phrase “community scientist” has become ubiquitous in modern parlance. Whether it’s sampling water from your local reservoir, scanning hours of footage for an elusive endangered species, or simply uploading photos of spring blooms to a plant identification app, the public has become the largest producer of natural history data in history.

But do these data have downsides? And how might those downsides affect the ability to use these data to understand the risks of climate change to many different species? These are the questions that Tess Alexander posed as part of a continuing research project in the lab of GCC affiliate Meryl Mims, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences in the College of Science since 2017.

The Mims Lab investigates how biological and environmental factors influence the vulnerability of species to climate change. They use data from diverse sources, from population genetics to publicly collected natural history data. Joining the lab in 2019 as a biological sciences major with a minor in national security and foreign affairs, Alexander excelled in the lab environment, both as an integral team member and later as an independent researcher. “Tess approached her research with curiosity and initiative, much like a graduate student,” says Meryl.

Working closely with IGC fellow Chloe Moore, Alexander sought to determine whether occurrence data (or a record of a species’ exact location in space and time) used in combination with environmental data to develop species distribution models (SDMs) can be used to predict where a species likely occurs without inherent bias. She used R programming to compare occurrence points of two frog and one toad species in the United States from two publicly sourced databases to examine the quality and potential biases of these data.

When asked why this research was significant, she said, “It is crucial because these species play a major role in food webs, consequently impacting humans.” Her results suggested that occurrences derived from these databases are biased towards human collection efforts in such areas as parks and population centers, and SDMs using these data need to account for these biases to better predict distribution of biodiversity.

“Being able to evaluate the reliability of large-scale, opportunistically collected species data will allow us to examine questions related to data over- and under-representation across space, the extent and spread of invasive species, and changes in species distributions over time,” said Mims.

The next steps of the project will include exploring other species and occurrence databases and correcting for the biases Alexander discovered. And while Tess has graduated this past spring, she plans to continue using her analytical skills in the public sector, not too far from her hometown of McLean, Virginia.

From trapping the tooth fairy as a young child to trapping mosquitoes for research in order to better understand the impacts of climate change on disease vectors, Ash VanWinkle has always examined the world through the lens of a scientist. Her initial scientific curiosity was sparked many years ago, after receiving a circuit set as a Christmas gift. “I used it to build an alarm to catch my dad being the Tooth Fairy when I lost a tooth, and from then on I was curious about all the things (mischievous and otherwise) science could do,” she recalled.

This natural interest in science eventually led her to join the Virginia Tech community as a biochemistry major with a minor in chemistry. VanWinkle joined the lab of Chloé Lahondère in 2020 and began working with graduate student Lauren Fryzlewicz (a previous recipient of a GCC Undergraduate Research Grant), researching how climate change can impact disease vectors such as mosquitoes. Vanwinkle studied the development of an attractive toxic sugar bait for the control of Aedes j. japonicus.

“I am really grateful to the GCC for supporting undergraduate research and for supporting Ash’s project in particular,” Lahondère said. “VanWinkle’s project focuses on an invasive mosquito species for which no control method currently exists.”

The invasive species Aedes j. japonicus is a potential vector of West Nile virus, a disease with no approved treatment or vaccine that impacts millions worldwide, and is competent for several other viruses including dengue. “With warming climates,” VanWinkle said, “the active range for mosquitoes is growing, and we hypothesize that drier climates will encourage more mosquito activity.”

Using the GCC grant funds, she has been able to address this problem by creating and testing novel attractive toxic sugar baits (ATSBs) for mosquito control. To test this, boric acid, which is lethal to mosquitoes, was mixed with various solutions of sucrose and various fruit sugars to use in feeding assays. VanWinkle found that survivability was much lower in mosquitoes fed solutions containing boric acid compared to those who weren’t, proving the efficiency of ATSBs in this invasive species. The next steps for this project will be to couple the ATSBs with a suitable trap and test its efficiency in the field during warmer months.

After graduating this year with a publication in the works and the Dennis Dean Undergraduate Research Symposium Policy Award in tow, VanWinkle is entering Virginia Tech’s master’s in biochemistry program.

VanWinkle reflects back on one of her most important influences, “I wouldn’t have had any opportunity to do any of this without my dad. It was his funds received through the Post-9/11 GI-Bill that allowed me to go to college, and he has supported me in more ways than I can count over the past three years.”

Supported projects address basic and/or applied aspects of global change science, engineering, social science and the humanities and are sponsored by a GCC Faculty mentor. Interested students and GCC faculty affiliates can find more information about the grant here.

-written by Heather Drew