This lab teaches students to debunk false information

Sophomore Evan Allen knows his way around Reddit’s r/WallStreetBets, an online forum where millions of users gather to talk about the stock market.

Along with a team of three other students, who call themselves the Disinformation Defeaters, Allen has spent much of his spring semester scouring the subreddit for inaccurate information. The work counts toward the Virginia Beach native’s grade in Virginia Tech’s inaugural Open Source Intelligence Lab course, which teaches students how to analyze publicly available sources to find misinformation (false information) and disinformation (false information that’s deliberately spread).

The r/WallStreetBets forum became infamous earlier this year when its members bought up shares in GameStop, a video-game retailer, temporarily sending the stock skyrocketing.

"We're investigating misinformation there because it's a very high value target,” said Allen, a computer engineering major. “If you can convince a bunch of people on the internet to go take certain actions in the stock market, then maybe you can make money, so we’re looking at that.”

Massive interest

Kurt Luther, associate professor of history and of computer science at Virginia Tech, created the interdisciplinary Open Source Intelligence Lab course with Aaron Brantly, assistant professor of political science, and David Hicks, a professor in the School of Education.

“As misinformation has become an increasingly severe problem in society, I thought there might be an exciting opportunity to teach a course to help students think about misinformation, learn to identify it and debunk it,” Luther explained.

It’s a subject students want to learn more about, added Brantly. “The 2016 election and everything since then has just spurred a massive peak in interest in how people are taken in by various forms of misinformation,” he said.

Teaching students about open source intelligence (OSINT) demands an interdisciplinary approach, Luther explained. “This is a topic that's much bigger than just one discipline,” he said.

Brantly works on issues related to cybersecurity from multiple angles, including human rights and development, intelligence and national security, and military cybersecurity. Hicks, meanwhile, frequently tackles projects looking at the interaction between humans and computers.

“Being able to have other faculty members contribute their perspective has really enriched that class,” Luther said.

The interdisciplinary nature of the course is what prompted Brantly to call it “the ideal of what Virginia Tech offers."

“It’s the idea of putting together people from multiple different disciplines to solve a single problem that really impacts our human security,” he said.

Hands-on learning

Each week, the class meets virtually for three hours. Luther logs on from Arlington, where he works at the Virginia Tech Research Center. Most of the students, as well as Brantly and Hicks, are based in Blacksburg.

In a normal year, students and professors would gather in classrooms in Blacksburg and Arlington and would connect with one another via video. During the pandemic, of course, everyone logs in online from a home office or residence hall. “I actually saw that as a strength,” Luther said. “Or, at least, I was looking at the silver lining in the situation.”

When they designed the Open Source Intelligence Lab course, the trio of professors knew they didn’t want to spend three hours lecturing while students scrambled to take notes. Instead, class time is spent with students breaking into groups to discuss readings about OSINT, watching technology demos, completing classroom exercises and participating in capture-the-flag events, where teams of students compete against one another, doing things like seeing who can debunk the most misinformation on social media.

“I am always looking forward to coming because there's always something new to learn,” said Mehak Kamal, a junior majoring in computer science.

Working remotely, Luther has found, makes it easy to break into small groups for discussions and exercises. Since all of the classes are automatically recorded, they can be accessed by students at any time. “We're doing a lot of technology demos,” Luther said, “and those can be useful to refer to later.”

Another distinctive aspect of the course: It’s designed for both undergraduate computer majors and political science majors. A handful of graduate students also enrolled in the class, which has about 50 students.

When class members put together their teams for the lab, they divided into groups of four. Each team included at least one computer science student and one political science student.

Kamal finds working with students from other departments “really exciting,” and she’s noticed the political science students tend to tackle problems with a social-sciences approach.

Luther also enjoys teaching students from different disciplines. “I've been able to see the teams of students from different majors working together, working through problems and benefiting from each other's expertise in ways that I think are really exciting,” he said.

While Allen’s team uses OSINT skills to hunt on Reddit for misinformation, the class’s other teams are examining information on topics including COVID-19 vaccines, human rights in China, election fraud and security, and climate change.

“All the practice that we do is all on real topics and real investigations, so it feels meaningful,” Allen said.

Luther spends half of the semester teaching students to build new OSINT tools based on the analysis techniques they learned in the first part of the course.

“One of the cool things about doing this in interdisciplinary student teams is that the political science students are learning to contribute to software development projects while the computer science students are incorporating the domain knowledge and real user needs voiced by the political science students,” Luther explained.

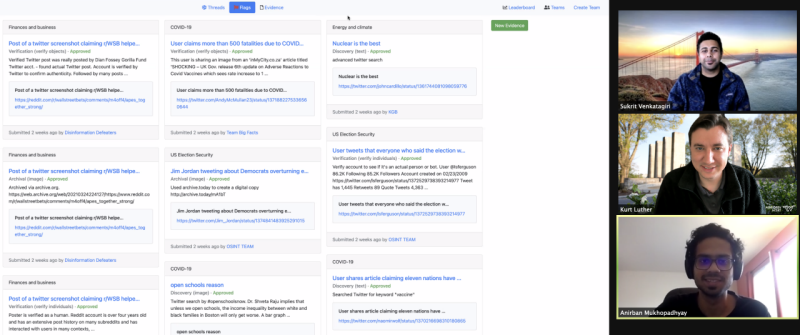

To aid with the capture-the-flag competitions, Anirban Mukhopadhyay, a computer science graduate student and the class’s teaching assistant, partnered with graduate student Sukrit Venkatagiri to build software that runs the competitions. The software allows students to form teams, keeps track of their points and submit their analyses.

“We've created this whole infrastructure to allow the students to both collaborate and compete, and it's specifically focused on the unique challenges of misinformation,” said Luther.

Each week, Mukhopadhyay and Venkatagiri make changes to the software based on feedback they receive from students.

A seed grant from Virginia Tech's Data and Decisions Destination Area covered the cost of employing Sukrit to help build the software and to conduct an evaluation of the course.

Currently, the pair is working to add a feature that allows teams to collaborate using OSINT software tools designed by the students. “So we can help them better in their investigation,” Mukhopadhyay said.

Healthy skepticism

Before enrolling in the Open Source Intelligence Lab, Allen felt confident he could pick out misinformation on social media.

Midway through the semester, though, he realized some of the people who intentionally spread disinformation may be more sophisticated than he previously thought. “I’m not even as good at that as I thought I was,” he said.

And that is music to Luther’s ears. “I want all the students to leave the course well prepared to be more skeptical consumers of the information that they encounter in the world,” he said.

— Written by Beth JoJack

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)