Virginia Tech researchers receive a $2 million NIH grant to develop Zika virus vaccine

Flaviviruses — a group of viruses transmitted by ticks or mosquitoes — infect an estimated 400 million people annually with diseases like yellow fever, Dengue fever, West Nile virus, and, most recently, Zika virus.

Outbreaks of Zika virus, a flavivirus originating in Africa, were once rare and isolated events. But in 2015, it arrived in the Americas and rapidly spread to 27 countries within the span of a year.

Zika virus outbreaks have now been recorded throughout Southeast Asia, the South Pacific, South America, and Central America. To protect the health of billions of people at risk and prevent future outbreaks, a team of Virginia Tech researchers received a $2 million R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health to develop a safe, effective, single-dose vaccine candidate for Zika virus.

“This grant focuses on a new strategy that we developed to produce safe and effective flavivirus vaccines. It aims to prevent the emergence of these viruses — in this case Zika virus — in humans,” said Jonathan Auguste, an assistant professor in the Department of Entomology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Irving Allen, an associate professor, and X.J. Meng, a university distinguished professor, both from the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, are joining Auguste as co-investigators. With this grant, they will move into testing the safety and effectiveness of this vaccine candidate.

“The Auguste Lab has recently developed an exciting and highly innovative vaccine platform that has the potential to revolutionize vaccine development against other flaviviruses infecting humans and other animals. The flaviviruses pose immense public and veterinary health burdens, so developing effective vaccines against flaviviruses such as the Zika virus will help more effectively prevent and control disease outbreaks,” said Meng, whose expertise is in virology and vaccinology.

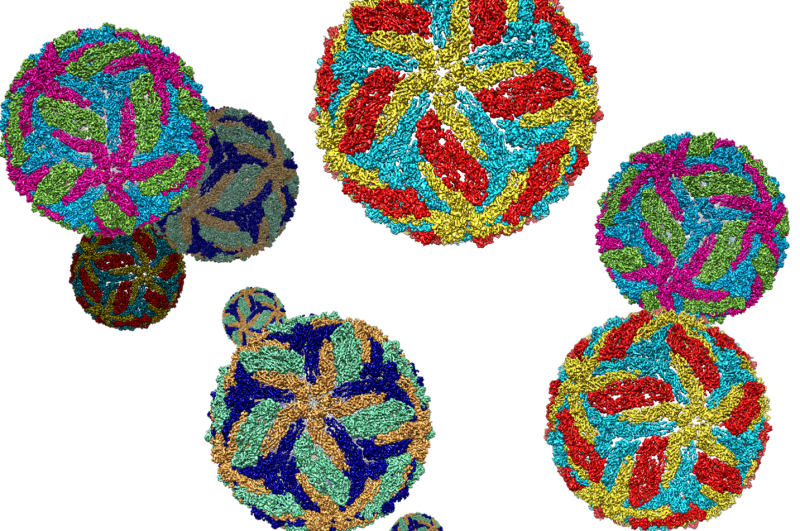

To develop their vaccine platform, the Auguste lab isolated a virus from mosquitoes that is able to replicate only in mosquito cells — meaning that it is unable to infect mammals. Together with James Weger-Lucarelli from the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, they substituted the proteins that code for the virus’ behavior with proteins that make it look like a pathogen. Ultimately, they created a virus that looks identical to Zika virus but is unable to replicate.

“It has a lot of advantages because it is exceptionally safe — if it can’t replicate, it causes no disease. It can’t acquire mutations to cause disease because its replication is defective. It grows really well in cell cultures, so it’s easily produced. You can get a really good immune response with just one vaccination,” said Auguste, who is also an affiliated faculty member of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute and Center for Emerging, Zoonotic, and Arthropod-borne Pathogens.

(from left to right): Krisangel Lopez, Dawn Auguste, Jonathan Auguste, Will Stone, Danielle Porier, Manette Tanelus

In vaccine development, there is a trade-off between safety and immunogenicity, the ability to produce an immune response. A killed-virus vaccine is exceptionally safe but may take several doses to produce a strong enough immune response to protect the individual. On the other hand, a live-attenuated virus vaccine is made from a weakened form of the virus, so the reaction it produces is more immunogenic and effective. By combining elements from both vaccine development strategies, Auguste, Allen, and Meng developed a platform that safely produces a robust enough immune response with just a single dose.

“This project is exciting because it will utilize a novel strategy to generate and validate a vaccine candidate against Zika that should have the advantages of the live-attenuated vaccine and the safety profile of the inactivated vaccine,” said Allen, who will be contributing his expertise in immunology to understand how the vaccine functions so effectively.

The team has already seen success in testing their vaccine platform in mice by demonstrating that it completely protects against any replication of the virus in the blood. Plus, their vaccine addresses one of the most severe effects of a Zika infection — microcephaly. It occurs when a mother infected with Zika transfers the virus to the fetus, which results in the shrinking of the baby’s head and poor brain development. But this vaccine platform “completely protected mice from in-utero Zika transmission,” said Auguste.

In the next steps of vaccine development, Auguste and his colleagues will need to run some preliminary studies and compare their vaccine with other vaccine candidates.

“I am looking forward to comparing my platform against other platforms that are already in clinical trials. That direct comparison will give me a really good understanding of where this platform can fall. If this is a very good platform, it can serve as a foundation for producing vaccines that can protect you from multiple flaviviruses with just one single vaccination,” said Auguste.

If this is a platform worth pursuing, the researchers will then move into testing in higher-order animals, like nonhuman primates, to ensure the vaccine’s safety and efficacy. If all goes well, the vaccine will later move into clinical testing.

A treatment or vaccine for Zika virus and other flaviviruses does not exist yet. Given the recent emergence of flaviviruses and the public health threats they pose, Auguste and his colleagues are testing if their vaccine can also protect individuals against multiple flaviviruses.

“That’s really important in places like the tropics, where people go on vacation all the time. For example, in my home country of Trinidad and Tobago, we have yellow fever, Zika, and dengue all on the same island,” he said. “So, a vaccine like that isn’t just desirable — it’s necessary.”

- Written by Rasha Aridi