Virginia Tech scientists link rare medical condition to its cause

Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC researchers use zebrafish to understand puzzling disease

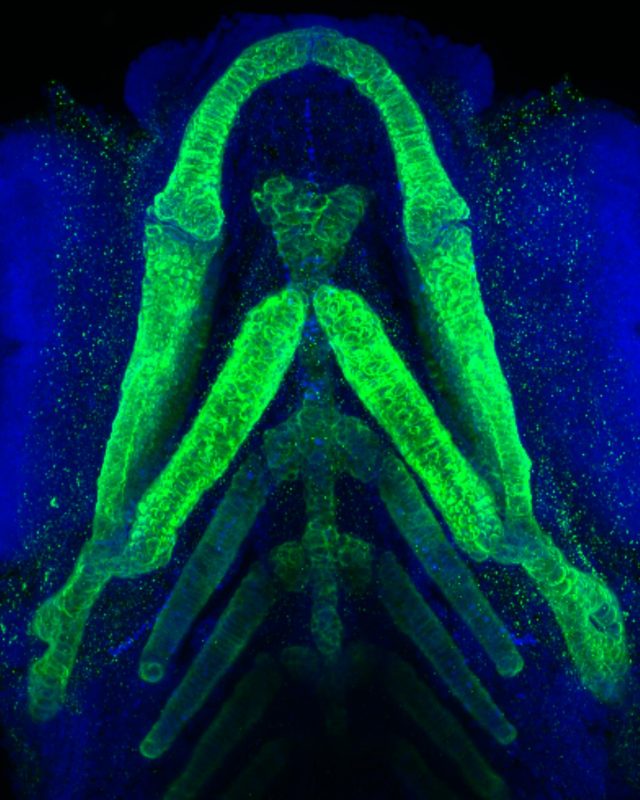

Using CRISPR genome editing in zebrafish, scientists with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC linked an undiagnosed human disease with a rare genetic mutation. The mutant zebrafish exhibited a striking increase in type II collagen, shown stained green in this underside view of lower jaw structures in a mutant zebrafish larva. Blue stain shows cell nuclei. Image by Kristin Ates/Augusta University/Virginia Tech.

Virginia Tech scientists with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC have manipulated genes to link an undiagnosed human disease with a rare mutation in the PHETA1 gene.

Using CRISPR genome editing and other research tools in zebrafish, the scientists found that zebrafish PHETA1-like proteins are necessary for renal function and craniofacial development in zebrafish — consistent with kidney and craniofacial problems observed in the human patient. The study was published in the current issue of Disease Models and Mechanisms.

The research began after a study of a 6-year-old girl identified through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Undiagnosed Diseases Program, which focuses on the most puzzling medical cases referred to the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

“When a family takes a child to a family physician and a specialist, and no one can figure what is causing the health problem, it creates a real burden,” said Albert Pan, an associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, who led an international team of investigators in the study. “We focused on this disease because it is hard to manage and difficult to treat because its underlying cause is unknown.”

In collaboration with the NIH team — along with an assembly of researchers from national and international institutions — Pan investigated how patient-associated mutations may contribute to the clinical phenotypes; in other words, the physical properties and appearance.

The patient, who had developmental delays and facial and renal abnormalities, had a mutated version of the PHETA1 protein. Researchers generated similarly mutated or deficient versions of the PHETA1-like proteins in zebrafish to find that they were interacting in a harmful way with OCRL, the causative protein for Lowe syndrome.

Deficiency in the PHETA1-like proteins resulted in impaired renal physiology and craniofacial development in zebrafish, resembling the renal and craniofacial characteristics in the patient. The craniofacial deficits in zebrafish were likely caused by a dysregulation of cathepsin K, which degrades collagen and is known for a role in osteoporosis.

A broad range of research groups collaborated during the study on matters of genome analysis, protein modeling, craniofacial development, and undiagnosed diseases.

“It was a complex, cross-disciplinary project that came together at the end,” said Pan, who is also the Commonwealth Center for Innovative Technology Eminent Research Scholar in Developmental Neuroscience and an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at Virginia Tech. “We linked a phenotype in an individual with an underlying gene. We have provided medical scientists a starting point to define a common syndrome and develop of preventions and treatments.”

The study involved researchers from the Greenwood Genetic Center, the Qatar Biomedical Research Institute, the Karlsruhe (Germany) Institute of Technology, Augusta University, and the Virginia Tech Advanced Research Computing Unit of the Division of Information Technology.

Several current and past members of the Pan lab participated in the research, including first author Kristin Ates, Tong Wang, and Manxiu Ma.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Commonwealth of Virginia Center for Innovative Technology, Virginia Tech, the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, and Augusta University.