Virginia Tech team working to preserve the treasure of Hawaii’s forests

A shoot of green rises on an expanse of recently cooled lava on Hawaii’s Big Island, the first evidence of seeds that have slipped through cracks and fissures to take advantage of moisture trapped in the new earth. The shoot will start as a shrub and then rise as a tree, producing brilliant flowers ranging in color from red to yellow. The flowers have adapted to close their stomata when toxic volcanic gases blow through, a plant version of holding one’s breath until the air clears.

This flowering evergreen, the ʻōhiʻa tree (Metrosideros polymorpha), is one of the most versatile and widespread plants in Hawaii, crucial to both the ecology and cultural history of the Pacific island chain. Today the ʻōhiʻa is under significant threat from two invasive fungal pathogens that can kill an 80-foot flowering giant in a matter of days. The fungus has ravaged forests on the Big Island and was recently discovered on Kauai.

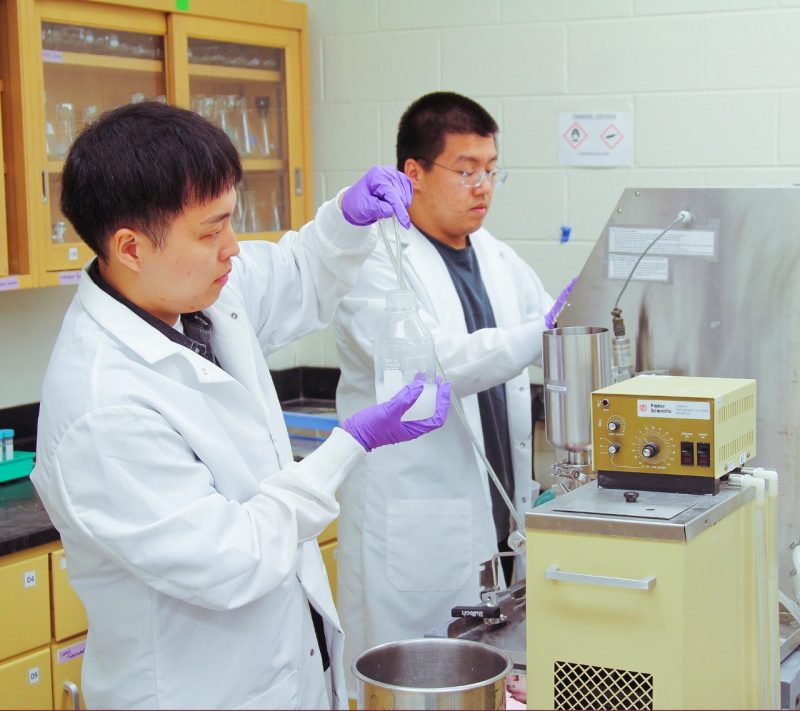

Scientists are now making efforts to contain the outbreak of this devastating pathogen and preserve Hawaii’s wood industry. To aid in that effort, and with the support of the USDA Forest Service, Professor Emeritus Marshall White and research scientist Zhangjing Chen of the College of Natural Resources and Environment are testing a portable method that uses a steam-and-vacuum system to sterilize ʻōhiʻa logs. Their efforts would allow foresters to move fallen trees and harvest logs, potentially slowing the spread the infection, termed Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death, while preserving Hawaii’s timber industry.

Using steam heat to save the ozone layer

White and Chen, both of the Department of Sustainable Biomaterials, have been researching steam-and-vacuum processes for killing off insect and fungal invaders in wood materials for the past five years. They have received more than $1.5 million in funding to test and refine the process of treating logs for transport.

“The current approved method in the U.S. for treating logs for import and export is with methyl bromide,” White explained. “The reason we’re trying to develop an alternative is because methyl bromide is a Class I ozone-depleting substance. It’s extremely dangerous and toxic to mammals.”

White and Chen’s process was initially developed to treat pallets and solid wood packaging more efficiently, but they have since expanded it to kill insects and fungi in logs, and even snail infestations in pallet loads of Mediterranean tile.

“The physics of steam and vacuum are fairly ideal for what we’re trying to do with these large pieces of wood,” White explained. “If you tried to treat a log with hot air, you’d dry it and degrade the wood. Steam is an ideal method of transferring energy to surfaces. We use vacuums to create pressure gradients to distribute heat effectively.”

The result is a process that carries less of an environmental burden and is more time efficient: while it takes 72 hours to fumigate an oak log with methyl bromide, the steam-and-vacuum treatment pioneered by White and Chen takes 8 to 12 hours.

The downside, White said, is the cost.

“This equipment is expensive," White said. "We’re talking about an initial investment of hundreds of thousands of dollars, whereas the initial investment in fumigation is significantly less — you just need tarpaulin and the gas itself, and some other basic pieces of equipment.”

White said that a recent economic analysis of the steam-and-vacuum method returned promising results. The analysis predicted a positive cash flow in the first year, and an annual rate of return of approximately 40% of the cost of equipment.

The goddess of fire

Aside from environmental considerations, the ʻōhiʻa tree plays a significant role in the cultural history of the islands. In Hawaiian mythology the ʻōhiʻa tree is revered as a symbol of young love and, perhaps, as a warning to not cross goddesses with fiery tempers.

“The tale is well-known in Hawaii,” White said. “The fire goddess Pele fell in love with a man named ʻŌhiʻa, but he was in love with a beautiful woman named Lehua. Pele got mad and turned ʻŌhiʻa into a tree. Lehua was distraught, so she went to the other gods and asked them to intervene, and after some deliberation, they decided to make her the flower of the tree.”

“And it’s a beautiful flower,” he added. “It’s just magnificent when the tree is in bloom.”

Native Hawaiians had multiple uses for the ʻōhiʻa tree. The hard, red-brown wood was used in the construction of homes as well as for tools, weapons, and the decking for outrigger canoes. The flowers and leaf buds were used to make leis, and the flower was used by native Hawaiians as a medicinal aid during childbirth. The tree remains a crucial building material.

“ʻŌhiʻa poles are still used in construction today,” White said. “The wood is very prized, not just by the native population for ceremonial structures but by nonindigenous people as well. It’s an extremely durable and beautiful wood.”

By land and sea

To work with this Hawaiian treasure and get their vacuum chamber to Hawaii, White and Chen had to take their project on the road and across the sea, quite literally.

“We put the vacuum chamber inside a 20-foot car trailer,” White explained. “Inside the trailer is a 7.5-horsepower vacuum pump and a 100-kilowatt electric steam boiler to create the steam. We also have various process controls and a data acquisitions system, which lets us monitor the temperatures of the logs externally and internally. All of that is on wheels.”

“Then we drove it across the country and shipped it by boat to Hawaii,” he said.

The fact that the chamber is portable is an added benefit, since it can reach forested areas where Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death has already occurred.

“Hawaii will not allow the movement of ʻōhiʻa logs and lumber right now because the process of removing dead trees spreads the fungus, so that’s a huge issue,” White explained. "You have parts of forest where this fungus exists that cannot be cleared, because you can’t move the logs. Right now, your only option is to burn the trees or bury them.”

Perfecting the process

To destroy the fungus, the logs are placed inside the vacuum chamber. The atmosphere is dropped to 15% air, and then saturated steam is injected into the chamber. White and Chen are testing different combinations of time and temperature to perfect the process for ʻōhiʻa logs.

To determine if the fungus survived the treatment, a team of pathologists from the USDA Forest Service and the University of Hawaii use “carrot baiting,” a method that involves taking a sliver of wood from the treated and untreated logs and putting it between two slices of carrot.

“Typically, we try to cultivate fungi on agar, but that doesn’t work well with these particular fungi,” White explained. “So we’re using carrots to see what will grow.”

The results are excellent: all of the ʻōhiʻa logs heat treated to 56 degrees Celsius using the steam-and-vacuum method have tested negative for the fungus responsible for Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death, an important first step in protecting Hawaii’s crucial forest ecology.

“This treatment will allow for the movement and utilization of materials from the ʻōhiʻa tree and a reduction in the dispersal of the fungus.” White said. “That’s the ultimate goal — to reduce the spread of the disease and protect this amazing tree.”