Medical student’s Fralin Biomedical research contributes to visual system understanding

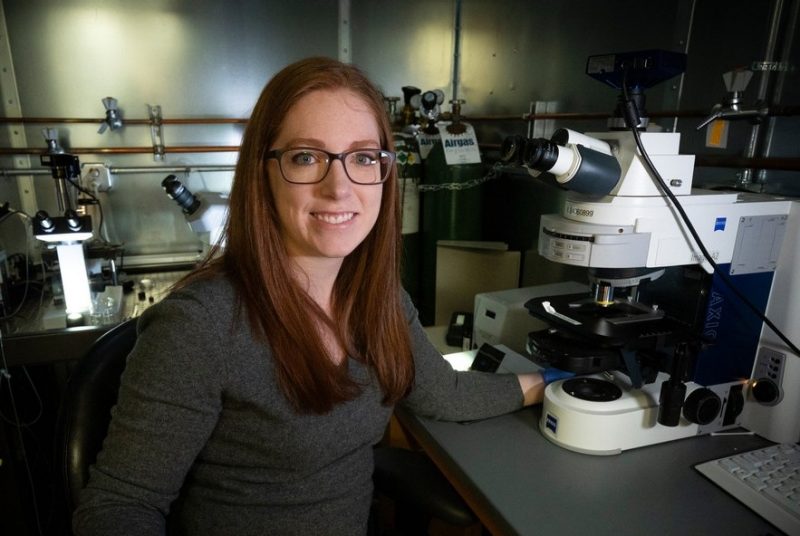

Soon after graduation from the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine in May, Gail Stanton has her sights set on residency in radiology. Her research on the visual system as both an undergraduate and medical student has helped inspire her path to that specialty.

While an undergraduate at the University of Washington in Seattle, Stanton did biochemistry research looking at the metabolic processes of photoreceptors in the eye. “We are such visual creatures and the visual system is so important to us,” Stanton said. “I came to medical school interested in building on what I learned as an undergraduate, but wanted to learn more about the brain part of the visual system.”

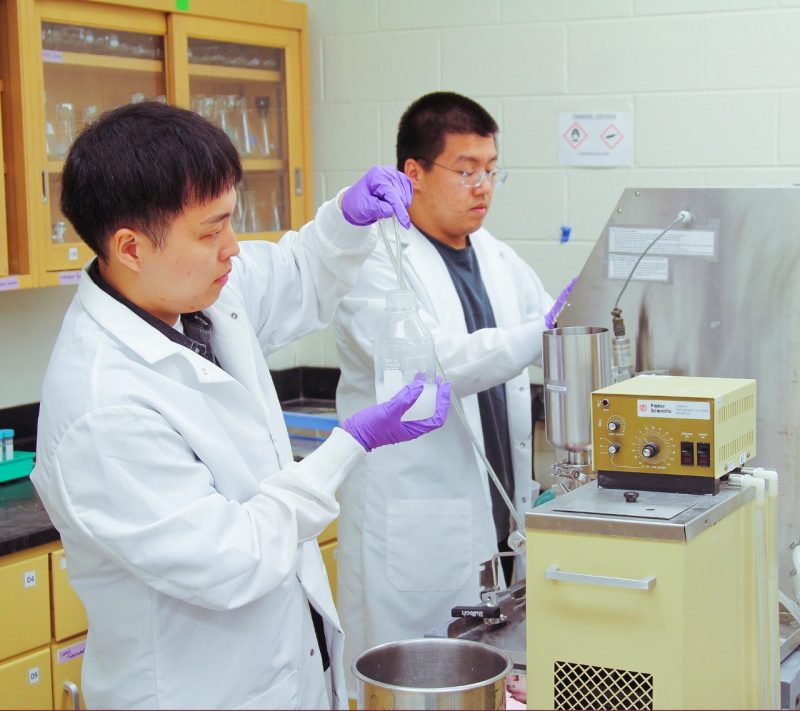

Stanton joined the Fox Laboratory at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, working under the mentorship of Michael Fox, associate professor and director of the Development and Translational Neurobiology Center at the institute.

In the lab, Stanton investigated development of the visual system. When cells in the eye gather information, it goes to the thalamus, a relay center of sorts that transmits the information to different areas of the brain. Stanton’s project looked at the development of connections within the thalamus. The lab had already discovered that on one side of the thalamus, synapses were smaller and less complex than on the other side. The lab wanted to figure out what led to the difference and if it could impact vision.

A graduate student in the Fox lab, Aboozar Monavarfeshani, found that each side expressed different levels of protein-coding genes. To investigate further, Monavarfeshani and Stanton each looked at two different proteins – Monavarfeshani at LRRTM1 and Stanton at NRN1. “If we take that protein away, will we lose those complex synapses or will we see other changes?” Stanton asked.

Stanton found no difference in rodent models lacking NRN1, but for Monavarfeshani, the complex synapses went away in mutants lacking LRRTM1.

A second half of the study looked at visual implications of taking away the two proteins during development. There were no visual deficits when NRN1 was removed, but as visual tests became more complex, there were visual deficits when LRRTM1 had been taken away.

This research used mouse models, so future research could see if this applies to other animals and humans that may connect to visual defects or deficiencies.

Stanton’s work in the Fox Laboratory led to a publication in eLife, a peer-reviewed open access scientific journal, as well as several presentations at national conferences. Stanton received a poster award in visual neuroscience at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology’s annual meeting.

“Gail approached research with enthusiasm and was intellectually engaged in not only her project but all of the visual system projects in the lab,” said Fox. “She worked incredibly hard in lab because she truly loves research, not because it was a medical school requirement. It was a real pleasure to have her in the lab.”

All students at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine are required to conduct original, hypothesis-driven research. In the first year, they receive research training and find a mentor. Over the next three years, they have dedicated time to work on their project.

“The research program drew me to apply here because research was something I enjoyed,” Stanton said. “Most medical schools encourage you to do research, but not all of them give you the resources and support to do it like we have here.”

Stanton is one of eight students in the class of 2019 who received Letters of Distinction for their research project. Each of them will give an oral presentation at the 2019 VTCSOM Medical Student Research Symposium. The rest of the class will give poster presentations. The symposium runs the afternoon of March 8. The public is welcome to attend and a live stream will also be available.

Beyond research mentorship, Stanton also found support during her medical school journey through the school’s local chapter of the Group for Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS). “I grew up with a single mother who always worked so hard to support me, my brother, and my sister. I also had people tell me that I shouldn’t go to medical school,” Stanton said. “Coming into medical school, I wanted to make sure I had a support system of other people and especially women who have made it into competitive fields in medicine and science.”

In a few weeks, Stanton will find out where she is headed for residency on Match Day, which this year will be March 15, when soon-to-be medical school graduates across the country find out where they will be placed to begin training in the specialty of their choice.

Stanton applied to radiology programs across the country. “One thing I learned through my research is that I love looking at what we are doing – using images and interpreting them,” Stanton said. “I think doing that for research, I realized I am a very visual person who likes to look at what I’m doing as opposed to just thinking about it. Radiology was a good fit.”

Now at the end of her medical school journey, Stanton can reflect on the process. “If you go into medical school for the right reasons, it is totally worth it,” Stanton said. “Towards the end of my second year, I got some advice that stuck with me: If you remember it is about the patients and not about you, everything else will fall into place.”