Home of the future takes first place at international competition

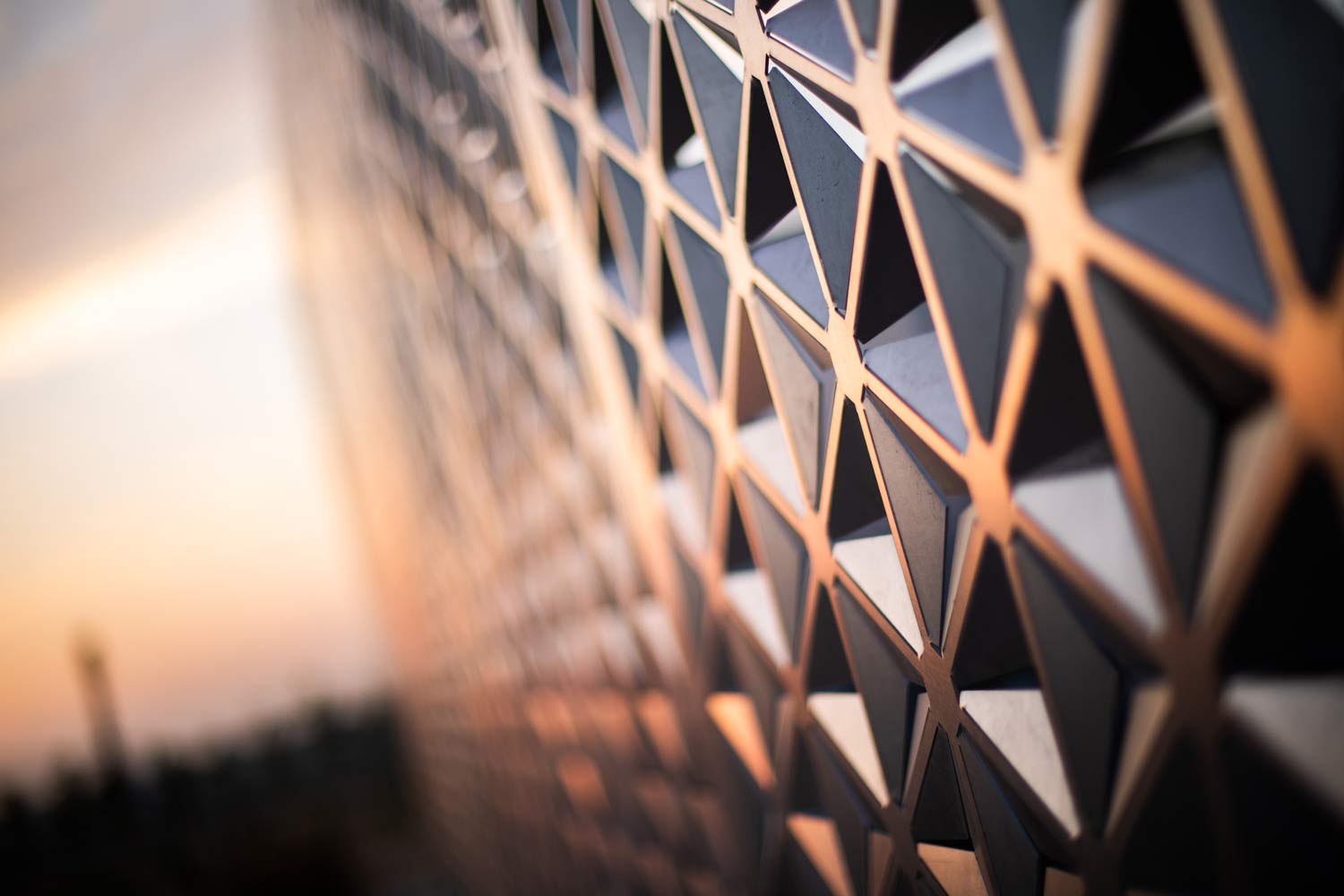

After years of research and development contributed by over 100 Virginia Tech students and faculty, the FutureHAUS Dubai team has officially built the world’s best solar home.

The lone American team earned a first-place victory over 14 other selected teams and more than 60 total entrants of the 2018 Solar Decathlon Middle East, a competition launched by the United States Department of Energy and the United Arab Emirates’ Dubai Electricity & Water Authority. The global competition aimed to accelerate research on building sustainable, grid-connected, solar homes.

The win follows nearly two decades of research and two years of accelerated development, overcoming a fire that burned down a previous iteration of the house, and more than a month spent in a desert in the outskirts of Dubai, where two dozen students and faculty erected the entire house.

The concept of FutureHAUS Dubai was brought to life through a university-wide effort, combining talents and research from Virginia Tech’s College of Architecture and Urban Studies, College of Engineering, Myers-Lawson School of Construction, Pamplin College of Business, College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, College of Science, and various centers and labs within.

“We have the most interdisciplinary team that we’ve ever had around any research project, and that’s what it takes. That’s the secret,” said Joe Wheeler, architecture professor and lead faculty of FutureHAUS Dubai. “That’s the formula to making something this amazing.”

The Solar Decathlon Middle East juries agreed. In addition to winning first place overall, the team earned top three in nearly all sub-contests: first place in architecture, first place in creative solutions, second place in energy efficiency, second place in interior design, third place in sustainability, and third place in engineering and construction.

According to team members, this success was largely due to a reliance on interdisciplinary knowledge. Each member contributed their unique set of skills, expertise, and life experience, filling in smaller parts of a bigger picture.

Josh Delaney, a first-year master’s student in architecture from Richmond, Virginia, said the team went out of their way to bring in as many disciplines to the project as possible.

“It’s the reason why we have computer science, engineering, landscape architecture, interior design, architecture — we have people from all different backgrounds. My background is in construction and construction management,” Delaney said, citing his years of professional experience in the construction industry and his recent entry to the architecture program. “I bring the real-world building experience."

Between the team members on the ground in Dubai and those in Blacksburg, navigating so many involved disciplines was a learning experience for the team members.

“I have never experienced this much interdisciplinary knowledge going back and forth every single day to get something done,” said Michelle Le, a recent architecture graduate and student architectural design leader on the team from Herndon, Virginia. “Learning how to work as a team and working almost as a big family to get something like this into fruition is — I think it was just incredible.”

Beyond the competition, FutureHAUS looks to revolutionize homebuilding

For a team that built the home, not just for the inaugural Middle Eastern competition, but to challenge the status quo of traditional homebuilding, the accolades validate what Wheeler calls “the new way to build and a new way to live” that FutureHAUS Dubai proposes.

Aspirationally, the concepts behind the home will, in the near future, address real, impending problems awaiting an increasingly crowded world with finite resources. The hurdle, Wheeler said, is overcoming a revenue-driven homebuilding industry that has little room for innovation and change.

Recently-graduated industrial and systems engineering student Kunal Gandhi of Lexington, Virginia (left), and fifth-year architecture student Philip Kistler of Fayetteville, West Virginia, work on moving bags of rocks from a truck. The white rocks helped reflect heat from the plants in the garden and added to the house's aesthetic.

At Virginia Tech, Wheeler said, the team was given the space to innovate, without the pressure of turning an immediate profit. In turn, companies have been able to partner with and provide funding and gifts-in-kind for the team to use the house as a test bed for new ideas that they may not otherwise be able to explore.

“At the university, we cannot propose the future of building without collaboration with industry,” said Wheeler, also a co-director of the Center for Design Research in the School of Architecture + Design. “At the same time, the industry is going to have a hard time proposing what the house of the future is because they’re kind of stuck into a business model that has to generate profit.”

With the full support of the team’s industry partners, including such top sponsors as Dupont, Dominion Energy, and Kohler, the team sought solutions to save water and energy, eliminate waste in the homebuilding process, and ensure house inhabitants can age in place using smart and accessible technology.

It’s what attracted Dominion Energy’s now-retired executive vice president and chief innovation officer David Christian, a Virginia Tech mechanical engineering alumnus from the class of 1976 who spent the last week of the competition with the team in Dubai.

“The house reflects a tremendous amount of thought and work, all kinds of details and all kinds of innovations,” Christian said. “Dominion is an innovative company, and becoming even more innovative as we speak, so participating in a project like this — it’s just a double benefit. It’s win-win.”

What the FutureHAUS proposes

Traditional home building involves arriving at a location with raw materials that require assembly on a site that is subject to weather and uncontrollable working conditions. FutureHAUS, however, was built entirely in a lab as separate but compatible “cartridges” that are equipped with the walls, floors, ceiling, wiring, plumbing, and finishes all in one.

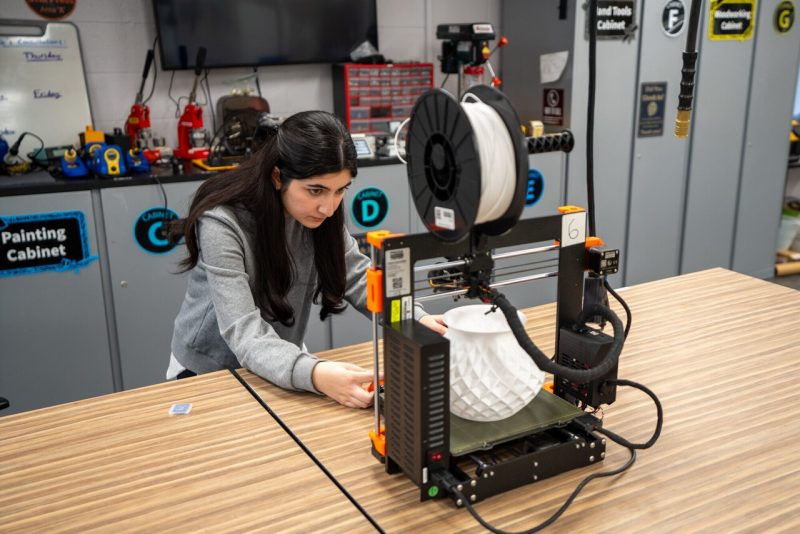

The customizable cartridges can be shipped to a location — in the case of Solar Decathlon Middle East, on only five trailers thanks to the work of industrial and systems engineering students — and easily put together with a plug-and-play approach.

“Our vision for this house will eventually be to create it on a mass production scale. Just like Henry Ford came and revolutionized the automobile industry by creating assembly lines and mass production techniques, we’re hoping that something similar can happen with this house,” said Rachel Carie, a recent industrial and systems engineering graduate from Bristow, Virginia.

Through the work of electrical and computer engineering students and the world-renowned Center for Power Electronics at Virginia Tech, FutureHAUS Dubai created an electric spine that connects the houses’ cartridges and links them to the mechanical room that contains the electrical systems and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system.

Senior computer engineering major Matt Erwin from Chesapeake, Virginia, said the team took an innovative stance in the mechanical room, rejecting the traditional approach of using the components of their electrical systems from only one company.

“If you look around, everyone has all of one company for their system,” Erwin said. “So instead, we were able to make kind of a Frankenstein system. We were able to pick and choose the best of each one to make us the most efficient.”

If the method is adapted and scaled up by the homebuilding industry, homes could be built in mass quantities at higher quality and more energy and cost efficient. Tradespeople like inspectors, electricians, and plumbers could all work collaboratively at one factory, converging disciplines constantly throughout the homebuilding process and yielding a better product.

“Through the FutureHAUS project, we’re trying to find a better way of simplifying the process, bringing it into a more controlled environment,” said Bob Schubert, associate dean for research in the Virginia Tech College of Architecture and Urban Studies and faculty member of FutureHAUS Dubai. “By doing so, you can put things together with better quality and in a shorter time frame.”

The efficiency of this modular, prefabricated building process was proven at Solar Decathlon Middle East when the team was the first to erect their structure in under two days.

They didn’t stop at just the walls and floors: The team was the first to connect their house to the communications network, first to set up the competition’s monitoring systems, and first to connect to the electric grid on site. The team was one of seven awarded bonus points in the competition for completing all required inspections by the end of the two-week construction period.

The timeline speaks for itself, explains Wheeler.

“I’m more excited than ever to see that this thing is really a solution to the future of how we build. This is the solution,” Wheeler said.

Living in the future

As smart technology increasingly permeates daily life, FutureHAUS sought to integrate secure smart systems into the house of the future, anticipating the needs of an increasingly connected but security-concerned population.

Led by the expertise housed in the Virginia Tech Department of Computer Science’s Center for Human-Computer Interaction, the house was equipped with 67 devices, including touch screen control panels, automatic sliding doors, a smart mirror that helps users find their clothes, a moveable wall that creates new floor plans using what the team calls “flex space,” and a sink created in collaboration with Kohler that can pour a precise amount of water for drinking or cooking needs.

Matt Tucker, a senior from Knoxville, Tennessee, who is studying electrical engineering and who works in the computer science lab, said the responsibilities expected of the group provided him with opportunities to actually implement concepts learned in the classroom into a real-life situation.

“Not only have I had the opportunity to actually put a lot of this stuff into practice, a lot of it is stuff I get to design,” Tucker said. “So I get to have input. I’m not just following a textbook or class curriculum. I’m coming up with some of these designs, some of this software, actually building it with a team — which is everything I hope to do when I graduate, when I go off and get a job.”

While the technology inside the house is evidently cutting-edge, FutureHAUS took an innovative approach to an area of the house perhaps unexpected: the garden.

“The inside of the house obviously integrates so many technological advances so seamlessly, so it might follow for some people that we would have something like a green wall or a green roof,” said Alexandra Schiavoni, a master’s student studying landscape architecture from Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania. “Though our garden seems very familiar, I think a lot of aspects of that are actually embedded in that are a lot of its greatest innovations.”

But rather than integrate more technology into the garden, Schiavoni and fellow landscape architecture master’s student Alex Darr from Lovettesville, Virginia, led a surprisingly different take on typical residential design. They incorporated native plants — including four 35-year-old, mature olive trees — instead of designing with annual plants and plants that require complex irrigation systems. Instead, plants were carefully selected to withstand the intensity of the desert heat with little water, in part due to strict competition rules on using water.

The garden embodies the essence of what FutureHAUS is: a home built for the people living in it. By bringing in the expertise of landscape architects who worked collaboratively with the architects and engineers, the garden became a transformative space in the house that fully considered its intended use.

It’s the same line of thinking behind bringing in Virginia Tech’s Megan Dolbin-MacNab, an expert on intergenerational family relationships from the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences who helped ensure the home would allow for accessible aging-in-place.

It’s why a team of marketing and business students helped tell the story of FutureHAUS Dubai through PRISM, a student-run advertising agency at Virginia Tech.

It’s why the team brought in students studying industrial and systems engineering in the College of Engineering who worked for a year on planning the most efficient method of shipping the house 7,286 miles from Blacksburg to Dubai.

And it’s why a team of electrical engineers and researchers from the Center for Power Electronics built an energy system so efficient, the house can sell energy back to the grid.

With hundreds of hands on the house over the past two decades of research, it’s a list that only scratches the surface. But one theme remains consistent: the students and faculty who worked on the project are fueled by the belief that FutureHAUS is what lies ahead.

“We have always believed in this concept, but now the world believes in this concept as well,” said Laurie Booth, a fourth-year architecture student from Charlotte, North Carolina, and student team lead of FutureHAUS Dubai. “[The concepts proposed by FutureHAUS are] all things that, now that we’ve built it, seem very real, seem very possible, which excites me the most: that maybe someday, thousands of people could live in a house like this.”

With the competition behind them, that’s what they hope is ahead. The team has already begun researching what it would take to scale up production in a factory setting. A new team of industrial and systems engineering students is exploring a concept of a manufacturing facility for building these types of houses.

For now, the team is celebrating a hard-earned victory in Dubai, thousands of miles from home. In the coming days, they will have to take FutureHAUS apart and ship it home.

But that’s a thought for another day.

“Every time I think about this project, I just can’t help but be amazed by my peers and that we did this,” Booth said. “I just feel forever in gratitude of the people that were on this project.”

Written by Erica Corder. Photos and videos by Erica Corder (unless otherwise indicated).

Editor's note: This story was updated with additional media assets after being published.